Organizing Your Own

Reader’s Guide

Who’s Who In The Book?

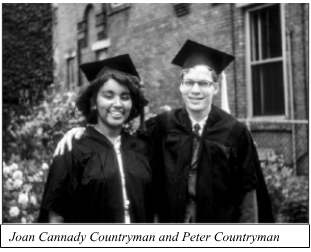

Joan Cannady Countryman

Joan Cannady hailed from Philadelphia and was Sarah Lawrence’s student body president at the time when she helped to found the Northern Student Movement. A Black woman from an activist family, Cannady married Peter Countryman and helped to lead NSM in the early 1960s.

Peter Countryman

Originally from Chicago, Peter Countryman was a white student at Yale when he paused his studies in the early 1960s in order to become the first director of the Northern Student Movement (NSM). As NSM gravitated towards a Black Power framework and sought Black leadership, Countryman stepped down as head, and Bill Strickland became NSM’s first Black director. Countryman often worked alongside Joan Cannady, who he eventually married.

Bill Strickland

A Harvard graduate, Bill Strickland was NSM’s first Black director in the early 1960s and steered the organization as it moved from tutoring to community organizing. Strickland was the first leader of a Black Power organization that established a policy of having white people form a parallel group. In Detroit that group became People Against Racism, and Strickland advised it for years. He became an important guide and mentor for white activists in Detroit who sought to organize white people against racism.

Wilbert McClendon

Wilbert Clendon led the Adult Community Movement for Equality, which was Detroit NSM’s community organizing wing. McClendon was once described by Bill Strickland this way: “If it is at all possible to measure the progress of the Northern Student Movement, Wilbert McClendon is that progress.”

Dorothy Dewberry Aldridge

Dorothy Dewberry could boast major movement experience by the late 1960s. She had been an active youth in the NAACP and NSM. She became most associated with Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, whose Detroit office she led for years. The year after NSM asked white people to leave the group and build a parallel one, she made a similar declaration. “Whites have to begin to do jobs that Negroes cannot do,” she averred, “that is, to begin to work in their own communities.”

Frank Joyce

For several years, Frank Joyce was the white head of the Detroit NSM office, often supporting the local SNCC office too. When in 1965 NSM asked white members to leave and form a parallel group, Joyce played a major role in explaining this strategy to other white people and building the white fight for Black Power in Detroit. Aside from co-founding People Against Racism, he went on to be a major figure in the Motor City Labor League, which was the white parallel to the League of Revolutionary Black Workers.

Pat Murphy

Pat Murphy got involved in civil rights efforts – initially as a tutor and organizer for Detroit NSM – after she learned about the violence against civil rights activists in Birmingham in 1963. She helped to lead in the formation of Detroit NSM’s white parallel, People Against Racism, in 1965 and became one of PAR’s most dedicated and longest-serving members.

Douglass Fitch

Douglass Fitch moved to Detroit in 1968, after he had been a pastor-activist in California for some years. As the sole African American employee at the Detroit Industrial Mission (DIM), he both pushed DIM to confront white employers on their racism and was a bridge between DIM and the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement. He left DIM at the end of 1969, but his impact was felt for years in DIM’s affirmative action and “new white consciousness” trainings.

Bob Terry

Bob Terry was DIM employee who was most impacted by Douglass Fitch. A white man, Terry worked with Fitch to create a “new white consciousness” training that would complement Fitch’s “new black consciousness” training. In 1970, his provocatively-titled book For Whites Only was published, which codified the thinking that he and DIM promoted in their work.

Sheila Murphy

Sheila Murphy was only 20 years old when she was tasked with mounting a white response to an episode of police violence in Detroit. The initial protest she organized grew into a nearly all-white cop-watching group called the Ad-Hoc Action Group, which was active between 1968 and 1970. From there, she helped to found the Motor City Labor League but led a split from that group in 1972. Murphy married Kenneth Cockrel, a lawyer and leader of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers (and later, the Black Workers Congress).

Joann Castle

By the time she was a leader of the Ad-Hoc Action Group, Joann Castle was a housewife, activist, and mother of six. Her whole family became deeply involved in Ad-Hoc’s cop-watching program. Then, Castle took the lead in creating the Control, Conflict, Change Book Club in 1971, a political education program of the Motor City Labor League (the white parallel of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers (and later, the Black Workers Congress). Castle later married Mike Hamlin, a leader of the League and BWC.

Ken Cockrel

Perhaps one of the most famous lawyers in Detroit’s history, Kenneth Cockrel took on some of the most important and bold court cases of the 1960s and 70s. He was also synonymous with Black radical politics in the city. Alongside radical white attorney Justin Ravitz, he helped Black workers and the League of Revolutionary Black workers bring the fight for Black Power to the courts. When the League split in 1971, he joined the Black Workers Congress and pushed it to address the rise in police violence. He worked closely with Sheila Murphy as she spearheaded the Ad-Hoc Action Group and then the Motor City Labor League. The two later wed.

Justin Ravitz

As a young white lawyer, Justin Ravitz met his longtime legal-comrade Ken Cockrel in 1966 when they were both looking to interview witnesses to police violence. Within two years, Ra.vitz and Cockrel were both working for a new law firm that dared to take on some of the most difficult cases in Detroit, including cases against the Detroit Police Department. Ravitz and Cockrel advised the cop-watching group, Ad-Hoc Action Group, on how to conduct their police observation program from 1968 to 1970. After that, Ravitz became a part of the Motor City Labor League, while still working alongside Cockrel to defend Black workers, radicals, and police victims.

Mike Hamlin

It was Mike Hamlin who, in 1970, pushed the idea of a white parallel to the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. Hamlin had long been involved in radical Black politics, and now the League was facing immense state repression and internal problems. So, he enjoined white activists he had trusted for years – people associated with People Against Racism, the Ad-Hoc Action Group, and the Detroit Industrial Mission – to create a white group that would serve as a buffer between the League and violent repression. That group became the Motor City Labor League. Hamlin eventually married Joann Castle,.

Which Black Leaders and Groups Did The White Groups Take Direction From?

White-Led Groups | Black Leaders & Groups |

| People Against Racism | Bill Strickland and the Northern Student Movement (which later became the Afro-American Youth Movement) City-Wide Citizens Action Committee Also influenced by Dorothy Dewberry, Stokely Carmichael and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee |

| Detroit Industrial Mission | Reverend Douglass Fitch Also influenced by the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers |

| Ad-Hoc Action Group | Kenneth Cockrel and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers Poor People’s Campaign |

| Motor City Labor League | The League of Revolutionary Black Workers and the Black Workers Congress |